The Role of Metaphysics in Epistemological Theories

Have you ever paused to ponder the nature of reality? What does it mean to know something? These questions lie at the intersection of two significant branches of philosophy: metaphysics and epistemology. At first glance, they might seem like distant cousins, but in reality, they share a deeply intertwined relationship. Metaphysics, the study of what exists and the nature of reality, lays the groundwork for our understanding of knowledge—what we know, how we know it, and the validity of that knowledge. This article will explore how metaphysical assumptions shape our epistemological theories, ultimately influencing our beliefs about reality.

Metaphysics is a vast field that delves into the fundamental nature of reality. It raises profound questions about existence, objects, and their properties. Imagine metaphysics as the philosophical architect, laying the blueprints of reality. Key concepts such as being, substance, and causality are central to metaphysical inquiries. For instance, when we ask, "What is the nature of existence?" or "Do abstract objects like numbers really exist?", we are engaging in metaphysical exploration. These inquiries are not merely academic; they have real implications for how we construct our understanding of knowledge. If we assume that only physical objects exist, for example, it may limit our epistemological frameworks to empirical observations, sidelining other forms of knowledge.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge itself. It investigates the nature, sources, and limits of what we can know. Think of epistemology as the detective of philosophy—always questioning, analyzing, and seeking the truth. It encompasses various branches, including rationalism, which emphasizes reason as the primary source of knowledge, and empiricism, which asserts that knowledge comes from sensory experience. Each branch offers unique insights into how we understand knowledge and its acquisition. The significance of epistemology in philosophical discourse cannot be understated; it challenges us to reflect on our beliefs and the validity of our knowledge claims.

Knowledge can be classified into several types, each influencing epistemological theories and metaphysical assumptions. The main types include:

- Propositional Knowledge: Knowledge of facts or propositions, such as "Paris is the capital of France."

- Procedural Knowledge: Knowledge of how to perform tasks, like riding a bike or playing an instrument.

- Experiential Knowledge: Knowledge gained through personal experiences, which can be subjective and deeply personal.

Each type of knowledge interacts with metaphysical views, shaping our understanding of what it means to "know" something. For instance, if one holds a metaphysical view that reality is purely physical, it may lead them to prioritize empirical knowledge over experiential knowledge.

At the heart of epistemology lies the relationship between belief and justification. To say that one knows something often implies that they believe it to be true and have justification for that belief. But what role do metaphysical views play in this relationship? If one believes in an objective reality, their justification for knowledge might rely heavily on empirical evidence. Conversely, if someone holds a more subjective view of reality, their justification may come from personal experience or intuition. This interplay raises intriguing questions about the nature of knowledge and how our metaphysical assumptions can influence our beliefs.

The relationship between truth and knowledge is another area where metaphysics significantly impacts epistemology. Philosophers have long debated what constitutes truth and how it relates to knowledge. Some metaphysical perspectives argue that truth is absolute and objective, while others suggest it is more fluid and subjective. This divergence affects how we understand knowledge claims. For instance, if truth is seen as objective, then knowledge must align with that truth to be considered valid. However, if truth is subjective, then knowledge can be more personal and varied. This distinction is crucial for understanding different epistemological theories and their implications.

Every epistemological theory is built on certain metaphysical foundations. For example, a rationalist approach may rest on the belief that certain truths are self-evident and can be known through reason alone. In contrast, an empiricist view may assert that knowledge arises from sensory experiences and interactions with the world. These metaphysical underpinnings lead to distinct epistemological conclusions, influencing how knowledge is perceived and understood across different philosophical frameworks.

Exploring the dynamic relationship between metaphysics and epistemology reveals how metaphysical assumptions inform epistemological frameworks. For instance, a belief in a deterministic universe may lead one to adopt a more rigid view of knowledge, while a belief in free will may open up more subjective interpretations. This interplay shapes our understanding of reality and the nature of knowledge, prompting us to reflect on our beliefs and the foundations upon which they rest.

Various philosophical perspectives illustrate the interplay between metaphysics and epistemology. Rationalism emphasizes reason as the source of knowledge, while empiricism values sensory experience. Constructivism, on the other hand, posits that knowledge is constructed through social processes and interactions. Each of these perspectives offers unique insights into the relationship between metaphysical assumptions and epistemological theories, enriching our understanding of knowledge.

Current debates in philosophy continue to navigate the complexities of knowledge and reality. Thinkers grapple with questions about the role of metaphysics in shaping our understanding of knowledge. Are metaphysical assumptions necessary for epistemological theories, or can knowledge exist independently of them? These discussions are vital as they push the boundaries of our understanding and challenge us to reconsider our beliefs about knowledge and reality.

- What is the difference between metaphysics and epistemology? Metaphysics deals with the nature of reality, while epistemology focuses on the nature and limits of knowledge.

- How do metaphysical views influence our understanding of knowledge? Metaphysical assumptions shape the frameworks through which we interpret knowledge, affecting what we consider to be valid sources and types of knowledge.

- Can knowledge exist without metaphysical assumptions? This is a debated question; some philosophers argue that all knowledge is influenced by underlying metaphysical beliefs, while others contend that knowledge can be independent of these assumptions.

Understanding Metaphysics

Metaphysics is like the grand stage on which all of reality plays out. It dives deep into the **fundamental nature of existence**, tackling profound questions about what it means to be, what objects are, and the properties they possess. Imagine metaphysics as the blueprint of the universe, the underlying structure that informs everything we perceive and understand. It’s not merely about the physical world; it extends into the realms of **abstract concepts** and the very essence of being itself.

At its core, metaphysics can be broken down into several key concepts, each contributing to a richer understanding of reality. Here are some of the **cornerstone ideas** that metaphysicians explore:

- Ontology: This is the study of being and existence. It asks questions like, "What entities exist?" and "What does it mean for something to exist?"

- Identity and Change: How do we understand the identity of objects over time? What does it mean for something to change while still being the same thing?

- Space and Time: What are the nature and structure of space and time? Are they absolute, or are they relational?

- Causality: What does it mean for one event to cause another? How do we understand the connections between events in the universe?

These concepts are not just academic musings; they have profound implications for how we approach **epistemological inquiries**. For instance, if we believe in a **materialist ontology**—that only physical objects exist—our understanding of knowledge will be rooted in empirical observation. Conversely, if we adopt a **dualistic perspective**, acknowledging both physical and non-physical realities, our approach to knowledge might incorporate intuition or spiritual insight.

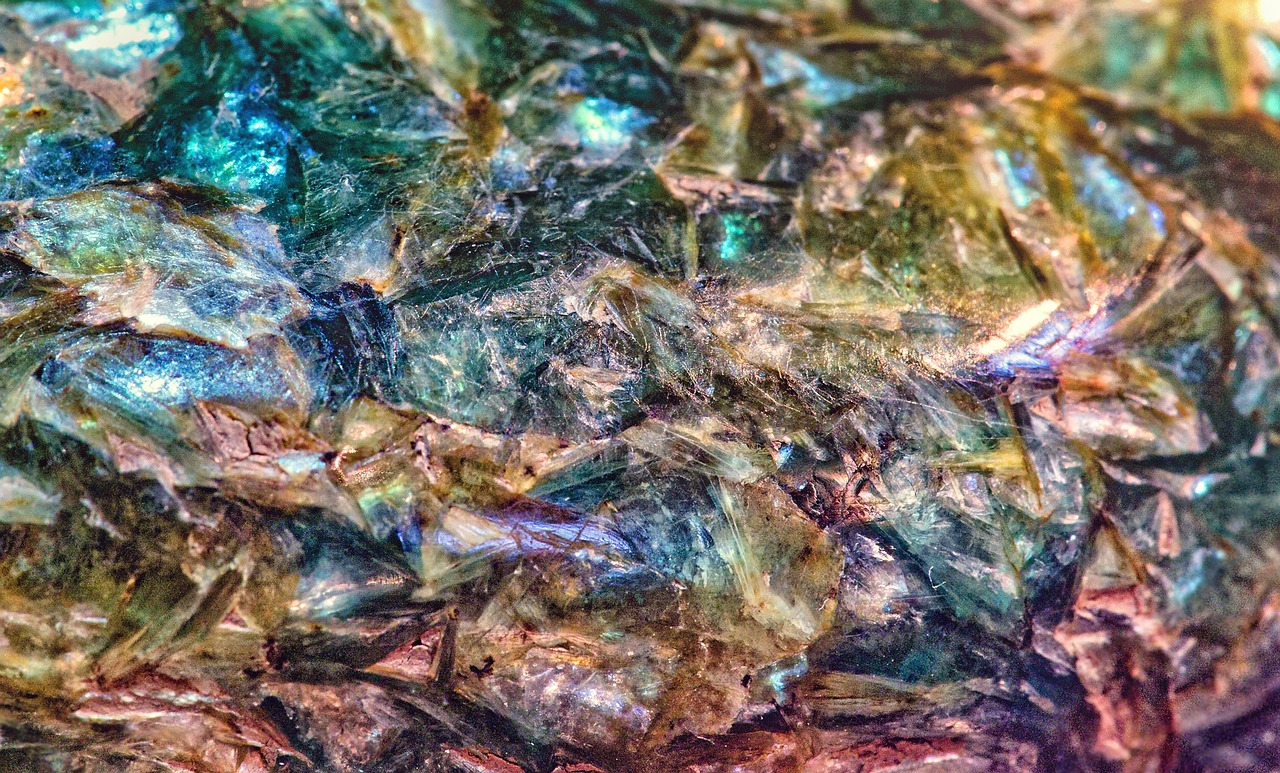

Moreover, metaphysics isn't static; it's a dynamic field that evolves with our understanding of the universe. As scientific discoveries unfold, they often challenge or reinforce metaphysical assumptions. For example, the advent of quantum physics has led to fascinating discussions about the nature of reality, prompting philosophers to reconsider the very fabric of existence. Are particles real, or are they merely probabilities? This interplay between science and metaphysics showcases how our understanding of reality is continually shaped and reshaped.

In essence, metaphysics serves as the foundation upon which our theories of knowledge are built. By grappling with questions about existence and reality, we set the stage for deeper inquiries into how we know what we know. As we move forward in this exploration, it becomes increasingly clear that metaphysical assumptions are not just abstract concepts; they are integral to our understanding of **knowledge, belief, and reality**.

Epistemology Defined

Epistemology is a fascinating branch of philosophy that dives deep into the essence of knowledge itself. At its core, it seeks to answer some of the most profound questions about what knowledge is, how we acquire it, and the limits of what we can truly know. Imagine standing at the edge of a vast ocean, with waves of uncertainty crashing against the shore of your understanding. That’s the realm of epistemology—navigating through the depths of belief, justification, and truth.

In the world of epistemology, knowledge can be classified into several categories, each offering a unique perspective on how we understand and interact with the world around us. For instance, we often distinguish between:

- Propositional Knowledge: This refers to knowledge of facts, such as knowing that Paris is the capital of France. It’s the type of knowledge that can be articulated in declarative sentences.

- Procedural Knowledge: This is knowledge of how to do something, like riding a bike or playing an instrument. It’s often acquired through practice and experience rather than through explicit instruction.

- Experiential Knowledge: This type of knowledge is gained through personal experience, emphasizing the subjective nature of understanding. It’s the kind of wisdom that comes from living through events and reflecting on them.

Each of these types of knowledge plays a crucial role in shaping epistemological theories. For example, propositional knowledge often serves as the foundation for logical reasoning, while procedural knowledge emphasizes the importance of skills and competencies in our understanding of reality. Experiential knowledge, on the other hand, highlights the significance of context and personal perspective in shaping our beliefs.

Furthermore, epistemology is not merely an abstract exercise; it has real-world implications. Consider how our beliefs and justifications influence our decisions and actions. The interplay between belief and justification is a central theme in epistemology. Belief refers to the acceptance that something is true, while justification relates to the reasons or evidence that support that belief. Together, they form the bedrock of what we consider knowledge.

To illustrate this relationship, think of a detective solving a mystery. The detective has a belief about who the culprit is, but that belief must be justified by evidence gathered during the investigation. If the justification is strong enough, the belief can be considered knowledge. However, if new evidence emerges that contradicts the initial belief, the detective must reevaluate their understanding. This dynamic process exemplifies how belief and justification are intertwined in our pursuit of knowledge.

In summary, epistemology is a rich and complex field that explores the nature, sources, and limits of knowledge. By examining different classifications of knowledge and the interplay between belief and justification, we gain a deeper understanding of how we construct our perceptions of reality. As we venture further into the realms of metaphysics and epistemology, we uncover the intricate web of assumptions that shape our understanding of existence and the very nature of truth.

Types of Knowledge

When we delve into the realm of knowledge, it becomes clear that not all knowledge is created equal. In fact, knowledge can be classified into various types, each with its own unique characteristics and implications. Understanding these distinctions is crucial because they significantly influence how we perceive and interact with the world around us. Let's explore three primary types of knowledge: propositional knowledge, procedural knowledge, and experiential knowledge.

Propositional knowledge, often referred to as "knowledge-that," is the type of knowledge that involves understanding facts and information. For instance, knowing that Paris is the capital of France or that water boils at 100 degrees Celsius are examples of propositional knowledge. This kind of knowledge is typically expressed in declarative sentences and can be easily communicated and shared. It forms the foundation for many epistemological theories, as it raises questions about the nature of truth and belief. How do we come to know these facts? What sources do we rely on to validate them? These inquiries lead us deeper into the philosophical waters where metaphysics and epistemology intertwine.

Next, we have procedural knowledge, which is often described as "knowledge-how." This type of knowledge is less about facts and more about the skills and competencies required to perform certain tasks. For example, knowing how to ride a bicycle, play a musical instrument, or cook a specific dish falls under procedural knowledge. Unlike propositional knowledge, procedural knowledge is often acquired through practice and experience rather than through formal instruction. This raises fascinating questions about the relationship between knowledge and action. Can one truly know how to do something without having practiced it? Here, the metaphysical assumptions about the nature of skills and learning come into play, challenging our understanding of what it means to "know."

Finally, we have experiential knowledge, which is derived from personal experiences and interactions with the world. This type of knowledge is inherently subjective and can vary significantly from person to person. For instance, your understanding of love, joy, or even pain is shaped by your individual experiences and cannot be fully conveyed through propositional statements. Experiential knowledge emphasizes the importance of context and personal perspective, which are crucial when considering epistemological theories. It invites us to ponder the question: how do our experiences shape our beliefs and understanding of reality? This is where the metaphysical exploration of consciousness and perception becomes essential.

In summary, the types of knowledge—propositional, procedural, and experiential—highlight the multifaceted nature of understanding and learning. Each type plays a vital role in shaping our epistemological frameworks and influences how we engage with metaphysical questions about reality, truth, and existence. By recognizing these distinctions, we can deepen our philosophical inquiries and appreciate the rich tapestry of human knowledge.

Justification and Belief

When we dive into the fascinating world of knowledge, two concepts stand out like beacons guiding us through the fog: justification and belief. Imagine you’re on a treasure hunt; belief is the map you hold, while justification is the compass that ensures you’re heading in the right direction. Without justification, our beliefs can easily lead us astray, much like following a faulty map that takes you to a dead end instead of the treasure. So, what exactly do these terms mean in the realm of epistemology?

At its core, belief refers to the acceptance that something is true or exists, even if it hasn’t been proven. It’s that gut feeling we often rely on, but here’s the catch: just because we believe something doesn’t make it true. For instance, you might believe that a certain restaurant serves the best pizza in town based solely on a friend's recommendation, but without tasting it yourself, that belief remains untested. This brings us to the concept of justification, which is all about providing solid reasons or evidence to support our beliefs. Think of justification as the sturdy foundation of a house; without it, the structure is weak and prone to collapse at the slightest challenge.

In epistemology, the interplay between justification and belief is crucial. To truly know something, we must not only believe it but also have a justification for that belief. This relationship can be illustrated through a simple table:

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Belief | The acceptance that a proposition is true or exists. |

| Justification | The evidence or reasons that support a belief. |

| Knowledge | Justified true belief; a belief that is true and justified. |

As we can see from the table, knowledge is often defined as a justified true belief. This definition suggests that for a belief to qualify as knowledge, it must meet three criteria: it must be true, the individual must believe it, and there must be sufficient justification for that belief. This triad forms a robust framework that challenges us to critically evaluate our beliefs and the justifications we provide.

But what happens when our justifications are flawed? Imagine you believe in a conspiracy theory based on shaky evidence. Your belief might feel strong, but without solid justification, it can crumble under scrutiny. This scenario highlights the importance of critically assessing not just our beliefs but also the foundations on which they rest. After all, a belief without justification can lead to misconceptions, and misconceptions can distort our understanding of reality.

In summary, the relationship between justification and belief is intricate and essential for forming a coherent understanding of knowledge. As we navigate through our beliefs, it’s vital to ensure that they are backed by sound justifications. This process not only strengthens our claims to knowledge but also enriches our engagement with the world around us. So, next time you find yourself holding a belief, ask yourself: what justifies this belief? Are my reasons solid enough to stand the test of scrutiny? By doing so, you embark on a journey toward deeper understanding and enlightenment.

- What is the difference between belief and knowledge?

Belief is the acceptance that something is true, while knowledge requires that belief to be true and justified.

- Can a belief be justified if it is false?

No, for a belief to be considered knowledge, it must be true. Justification alone is not enough if the belief is false.

- Why is justification important in epistemology?

Justification is crucial because it provides the evidence or reasons that support our beliefs, ensuring that our claims to knowledge are credible.

Truth and Knowledge

When we dive into the intricate relationship between truth and knowledge, it quickly becomes apparent that these concepts are not just academic jargon; they are the very foundation upon which our understanding of the world is built. Think of truth as the compass guiding us through the vast landscape of knowledge. Without a clear understanding of what is true, how can we claim to know anything at all? This relationship is essential for grasping how different metaphysical perspectives can shape our epistemological theories.

At its core, knowledge is often defined as justified true belief. This triadic relationship suggests that for something to be considered knowledge, it must meet three criteria: it has to be true, one must believe it, and there must be justification for that belief. However, this definition has been challenged by various philosophical arguments, most notably by the famous Gettier problem, which presents scenarios where individuals have justified true beliefs that we wouldn't intuitively consider knowledge. This leads us to question: if our beliefs can be justified and still not represent knowledge, what does that say about our understanding of truth?

Moreover, the metaphysical perspective one adopts significantly influences how one interprets truth. For instance, a realist might argue that truths exist independently of our beliefs or perceptions. In contrast, a constructivist might contend that truth is shaped by our social interactions and experiences. This fundamental difference can lead to vastly different epistemological conclusions. For example, if truth is objective and exists outside of human influence, then our pursuit of knowledge may focus on discovering these truths through empirical investigation. On the other hand, if we accept a subjective view of truth, our understanding of knowledge might lean more towards personal experiences and interpretations.

To illustrate this interplay further, consider the following table that summarizes different metaphysical views on truth and their implications for knowledge:

| Metaphysical View | Nature of Truth | Implications for Knowledge |

|---|---|---|

| Realism | Truth exists independently of beliefs | Knowledge is about discovering objective truths |

| Constructivism | Truth is constructed through social processes | Knowledge is subjective and context-dependent |

| Pragmatism | Truth is what works in practice | Knowledge is evaluated based on its practical applications |

In conclusion, the relationship between truth and knowledge is a dynamic and multifaceted one, deeply influenced by the metaphysical assumptions we hold. As we continue to explore these concepts, we must remain vigilant about how our beliefs shape our understanding of reality. After all, can we truly say we know something if we haven't examined the truth behind it? This ongoing inquiry not only enriches our philosophical discussions but also deepens our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

- What is the difference between truth and knowledge? Truth refers to the reality of a statement, while knowledge is the understanding or awareness of that truth.

- Can something be true but not known? Yes, something can be objectively true, but if no one is aware of it or believes it, it remains unknown.

- How do metaphysical views influence our understanding of knowledge? Different metaphysical perspectives can lead to varying interpretations of what constitutes truth, which in turn affects our epistemological frameworks.

Metaphysical Foundations of Knowledge

The concept of knowledge is deeply intertwined with metaphysical foundations, which serve as the bedrock upon which our understanding of knowledge is built. When we talk about metaphysical foundations, we are referring to the underlying assumptions about the nature of reality that influence our epistemological theories. These assumptions shape not only what we consider to be knowledge but also how we justify that knowledge. For instance, if one adopts a realist metaphysical stance, they might argue that knowledge is a reflection of an objective reality, where truths exist independently of our beliefs or perceptions. Conversely, a constructivist viewpoint might suggest that knowledge is constructed through social processes and individual experiences, highlighting the subjective nature of understanding.

To illustrate this relationship, consider the following key metaphysical positions and their implications for knowledge:

- Realism: Asserts that the world exists independently of our thoughts. Knowledge, therefore, is about accurately representing this external reality.

- Idealism: Proposes that reality is mentally constructed. Thus, knowledge is rooted in the mind's interpretations rather than an external world.

- Materialism: Suggests that only physical substances truly exist. Knowledge is then derived from empirical observation and scientific inquiry.

- Phenomenology: Focuses on subjective experience. Knowledge is understood through the lens of personal perception and consciousness.

These metaphysical positions not only inform how we define knowledge but also impact the methods we use to justify it. For example, a realist might rely on empirical evidence and logical reasoning to validate knowledge claims, while an idealist might emphasize coherence and internal consistency of beliefs. This divergence in approaches highlights the profound influence of metaphysical views on epistemological frameworks.

Moreover, the interaction between metaphysics and epistemology raises essential questions about the nature of truth. If knowledge is defined as justified true belief, then our understanding of truth must also be scrutinized through a metaphysical lens. Are truths universal and unchanging, or are they fluid and context-dependent? This inquiry leads us deeper into the philosophical debates surrounding the essence of knowledge and reality.

In summary, the metaphysical foundations of knowledge are crucial for understanding how different epistemological theories emerge. By examining these foundations, we can better appreciate the complexities of knowledge and the diverse perspectives that shape our beliefs about reality. As we navigate through the philosophical landscape, it becomes clear that our metaphysical assumptions are not just abstract ideas; they profoundly influence our everyday understanding of what it means to know.

- What is the relationship between metaphysics and epistemology?

Metaphysics provides the foundational assumptions about reality that shape our understanding of knowledge, which is the focus of epistemology. - How do different metaphysical views affect our understanding of knowledge?

Different metaphysical positions, such as realism or idealism, lead to distinct epistemological frameworks and methods of justifying knowledge. - Why is it important to study metaphysical foundations of knowledge?

Understanding these foundations helps us grasp the complexities of knowledge claims and the philosophical debates surrounding truth and belief.

The Interplay Between Metaphysics and Epistemology

The relationship between metaphysics and epistemology is a fascinating dance, one that shapes our understanding of reality and knowledge. It's like a two-sided coin; you can't have one without the other. Metaphysics, which delves into the fundamental nature of existence, provides the backdrop against which epistemological inquiries unfold. This interplay is crucial because the way we perceive reality influences how we understand knowledge itself. For instance, if we believe that reality is purely material, our epistemological frameworks will likely emphasize empirical evidence and sensory experience as the primary sources of knowledge.

On the flip side, if one adopts a more idealistic metaphysical stance, where ideas and consciousness play a central role, then knowledge might be viewed through a lens that prioritizes intuition, reason, or even spiritual insights. This dynamic relationship can be illustrated through various philosophical perspectives. For example, rationalism posits that reason is the primary source of knowledge, suggesting that metaphysical truths can be discovered through logical deduction. In contrast, empiricism emphasizes sensory experience, asserting that knowledge arises from what we can observe and measure in the physical world.

To further illustrate this interplay, consider the following table that summarizes key philosophical perspectives and their implications for the relationship between metaphysics and epistemology:

| Philosophical Perspective | Metaphysical Assumptions | Epistemological Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Rationalism | Reality is fundamentally rational and knowable through reason. | Knowledge is primarily obtained through logical reasoning and intellectual deduction. |

| Empiricism | Reality is grounded in physical phenomena and sensory experience. | Knowledge is derived from observations and experiments in the natural world. |

| Constructivism | Reality is constructed through social and cognitive processes. | Knowledge is seen as a product of social interactions and individual experiences. |

As we navigate through these philosophical waters, it's essential to recognize that the interplay between metaphysics and epistemology is not just academic; it has real-world implications. The way we understand knowledge influences everything from scientific inquiry to ethical considerations in society. For instance, if one adopts a metaphysical view that prioritizes objective truths, then the pursuit of knowledge might lean heavily towards scientific methodologies. Conversely, if one believes in subjective realities, then knowledge could be seen as more fluid and personal, impacting areas like education, policy-making, and even interpersonal relationships.

In contemporary debates, the dialogue between metaphysics and epistemology has gained even more traction. Thinkers are increasingly aware of how their metaphysical assumptions can either constrain or enhance their epistemological frameworks. The questions they grapple with are profound: What is the nature of reality? How do we know what we know? And, are there limits to our understanding that are dictated by our metaphysical views? These inquiries not only push the boundaries of philosophical thought but also encourage us to reflect on our own beliefs about knowledge and existence.

Ultimately, the interplay between metaphysics and epistemology invites us to explore deeper questions about our place in the universe. As we ponder these connections, we may find that our understanding of knowledge is as much about the questions we ask as the answers we seek. This relationship is a reminder that philosophy is not just an abstract discipline; it is a lens through which we can examine our lives, our beliefs, and the very nature of reality itself.

- What is the main difference between metaphysics and epistemology? Metaphysics deals with the nature of reality, while epistemology focuses on the nature and limits of knowledge.

- How do metaphysical views influence our understanding of knowledge? Our beliefs about what exists can shape how we define and pursue knowledge.

- Can epistemology exist without metaphysics? While they are distinct fields, epistemology often relies on metaphysical assumptions to formulate its theories.

Philosophical Perspectives

When we dive into the rich ocean of philosophical perspectives, we find ourselves navigating through various currents that shape our understanding of knowledge and reality. At the forefront, we have rationalism, which posits that reason is the chief source of knowledge. Think of rationalists as the intellectual architects who believe that our minds can construct knowledge independently of sensory experience. They argue that certain truths are inherent and can be discovered through logical deduction. For instance, the famous philosopher René Descartes famously said, “I think, therefore I am,” emphasizing the role of thought as the foundation of existence and knowledge.

On the flip side, we encounter empiricism, where the emphasis is placed on sensory experience. Empiricists like John Locke and David Hume argue that knowledge is primarily derived from what we observe and experience in the world around us. Imagine a painter who can only create art based on the colors and shapes they have seen; this is akin to how empiricists view knowledge acquisition. They contend that without sensory data, our understanding remains limited and speculative. This philosophical divide raises intriguing questions: Can we truly know anything without experiencing it first? Or is there a realm of knowledge that exists beyond our senses?

Then we have constructivism, a perspective that suggests knowledge is constructed rather than discovered. Constructivists argue that our understanding of the world is shaped by social interactions and cultural contexts. This viewpoint is akin to a sculptor who molds clay into a unique form, influenced by their experiences and the environment around them. Thinkers like Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky have contributed significantly to this theory, emphasizing that learning is an active process of construction rather than passive reception. The implications of constructivism challenge the traditional notions of knowledge as a static entity, prompting us to consider how our beliefs and knowledge are continuously evolving.

The interplay between these philosophical perspectives illustrates the complex relationship between metaphysics and epistemology. Each perspective not only offers a different lens through which we can view knowledge but also reveals how our metaphysical assumptions influence our epistemological frameworks. For instance, a rationalist might assert that knowledge is universal and unchanging, while an empiricist might argue that knowledge is contingent upon individual experiences. This divergence leads to rich discussions about the nature of reality itself: Is it a fixed entity waiting to be discovered, or is it a fluid construct shaped by our perceptions and interactions?

To further elucidate these philosophical perspectives, consider the following table that summarizes key characteristics:

| Philosophical Perspective | Key Proponents | Core Beliefs |

|---|---|---|

| Rationalism | René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza | Knowledge is primarily derived from reason and logical deduction. |

| Empiricism | John Locke, David Hume | Knowledge comes from sensory experiences and observations. |

| Constructivism | Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky | Knowledge is constructed through social interactions and cultural contexts. |

In summary, the philosophical perspectives of rationalism, empiricism, and constructivism not only highlight the diverse ways we can approach knowledge but also underscore the significant role metaphysical assumptions play in shaping our understanding of reality. As we continue to explore these ideas, we are reminded that the quest for knowledge is as much about the journey as it is about the destination.

- What is the main difference between rationalism and empiricism?

Rationalism emphasizes reason as the primary source of knowledge, while empiricism focuses on sensory experience as the foundation of understanding. - How does constructivism challenge traditional views of knowledge?

Constructivism suggests that knowledge is not merely discovered but actively constructed through social and cultural interactions. - Can metaphysical beliefs influence our understanding of knowledge?

Absolutely! Our metaphysical assumptions can shape how we perceive and categorize knowledge, impacting our epistemological theories.

Contemporary Debates

In the ever-evolving landscape of philosophy, the relationship between metaphysics and epistemology has sparked a myriad of contemporary debates. These discussions are not just academic exercises; they resonate with our everyday understanding of knowledge and reality. One of the central questions in these debates is: How do our metaphysical assumptions influence what we consider to be knowledge? Philosophers today are grappling with the implications of various metaphysical views, and how they shape our epistemological frameworks.

For instance, the rise of scientific realism has led to heated discussions about the nature of truth and existence. Proponents argue that our best scientific theories provide a true description of the world, while critics, often from a constructivist standpoint, assert that our understanding of reality is socially constructed. This clash raises essential questions about the limits of what we can know. Are we merely interpreting our experiences through a lens shaped by societal influences, or is there an objective truth waiting to be uncovered?

Moreover, the advent of postmodern thought has introduced skepticism towards grand narratives, including those put forth by traditional epistemological theories. The postmodern critique suggests that knowledge is not a universal construct but rather a product of specific cultural and historical contexts. This perspective challenges the very foundations of epistemology, prompting a reevaluation of how we define knowledge itself. In this light, metaphysical assumptions about the nature of reality become even more crucial, as they dictate the frameworks through which we interpret knowledge.

Another vibrant area of debate centers around the implications of quantum mechanics for metaphysical and epistemological discussions. The peculiarities of quantum phenomena have led some philosophers to argue for a fundamentally different understanding of reality—one that defies classical notions of determinism and objectivity. This has profound implications for epistemology, as it forces us to reconsider the nature of knowledge in a world that may not operate on the principles we have long accepted. Questions arise: Can we truly know anything in a reality that is inherently uncertain? and What does it mean for our beliefs to be justified in such a context?

In addition to these debates, the relationship between belief and justification continues to be a hot topic. The traditional view posits that for a belief to qualify as knowledge, it must be justified. However, contemporary thinkers are revisiting this notion, exploring whether justification is always necessary for knowledge. Some argue that there are instances where beliefs can be considered knowledge even in the absence of justification, particularly in cases of intuitive knowledge or expertise. This raises a fascinating question: Is it possible to know something without being able to articulate the justification behind it?

To encapsulate the essence of these contemporary debates, let’s consider the following table that highlights key philosophical positions and their implications for the metaphysics-epistemology relationship:

| Philosophical Position | Metaphysical View | Epistemological Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Realism | Objective reality exists independent of our perceptions | Knowledge is a reflection of this objective reality |

| Constructivism | Reality is socially constructed | Knowledge is contextual and varies across cultures |

| Postmodernism | Rejects universal truths | Knowledge is fragmented and subjective |

| Quantum Mechanics | Reality is probabilistic and uncertain | Challenges traditional notions of knowledge and justification |

As these debates unfold, it's clear that the interplay between metaphysics and epistemology is not just a theoretical concern but a practical one that affects how we navigate our understanding of the world. The questions raised in these discussions challenge us to think deeply about the nature of knowledge, belief, and reality itself. So, the next time you ponder what you know, consider the metaphysical underpinnings that shape your understanding. It might just lead you to a richer appreciation of the complexities of knowledge.

- What is the difference between metaphysics and epistemology?

Metaphysics deals with the fundamental nature of reality, while epistemology focuses on the nature and limits of knowledge. - How do metaphysical views affect our understanding of knowledge?

Metaphysical assumptions shape the frameworks through which we interpret and justify our beliefs, influencing what we consider to be knowledge. - Can knowledge exist without justification?

Some contemporary philosophers argue that in certain cases, beliefs can qualify as knowledge even without formal justification, particularly in intuitive or expert contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the relationship between metaphysics and epistemology?

Metaphysics and epistemology are closely intertwined. While metaphysics explores the fundamental nature of reality, epistemology investigates the nature and limits of knowledge. Essentially, metaphysical assumptions about what exists can shape our understanding of what we can know and how we justify our beliefs.

- How do different types of knowledge influence epistemological theories?

Different classifications of knowledge—such as propositional, procedural, and experiential knowledge—play a crucial role in shaping epistemological theories. For instance, procedural knowledge, which involves knowing how to do something, may lead to different epistemological conclusions compared to propositional knowledge, which is about facts and truths.

- What role does justification play in the formation of knowledge?

Justification is a key component in the formation of knowledge. It involves providing reasons or evidence for our beliefs. The interplay between belief and justification determines whether a belief can be considered knowledge. Metaphysical views can influence what counts as adequate justification, thereby affecting our understanding of knowledge itself.

- How does metaphysical perspective impact our understanding of truth?

Metaphysical perspectives on truth can significantly influence epistemological theories. For instance, if one adopts a correspondence theory of truth, which asserts that truth is what corresponds to reality, then their approach to knowledge will likely emphasize the importance of aligning beliefs with observable facts.

- What are some philosophical perspectives that illustrate the interplay between metaphysics and epistemology?

Philosophical perspectives such as rationalism, empiricism, and constructivism highlight the interplay between metaphysics and epistemology. Rationalists argue that reason is the primary source of knowledge, while empiricists emphasize sensory experience. Constructivists, on the other hand, suggest that knowledge is constructed through social processes, each perspective offering unique insights into how metaphysical assumptions shape our understanding of knowledge.

- What are some contemporary debates regarding metaphysics in epistemology?

Contemporary debates often focus on the relevance of metaphysics to epistemological discussions. Some philosophers argue that metaphysical assumptions are essential for understanding knowledge, while others contend that epistemology should be more concerned with practical aspects of knowledge without delving into metaphysical issues. These debates continue to evolve as thinkers grapple with the complexities of knowledge and reality.